These days, it is challenging to engage politically without any dependence on mass media. We depend on mass media to keep us politically informed and up-to-date so that we may feel like active participants, able to adequately engage in discussions about what to do and how. We all have our opinions, and now, thanks to social media, we are gifted individual podiums with microphones to announce our views to all who scroll by. For the first time, we’re living in a world where we have an outpouring of global information at our fingertips, constantly attuned to the grievances of faraway lands as if they were in our neighborhoods. It is ever important to discuss both the consequences and the benefits. Does mass media serve as a social narcotic, producing a generation of mass apathy, as presented by Lazarsfeld and Merton (1948)? Or is it a tool that can be used to help organize social action and rise against oppressive governments and regimes? Moreover, if both are true, can citizens harness the benefits of social media to formulate and engage in productive social action while remaining unaffected by its narcotizing powers?

In this essay, I will consider the concerns that Lazarsfeld and Merton held in the 40s and explore how these concerns have manifested in the age of social media through the lens of political engagement. I will discuss terms that have evolved from the times of Lazarsfeld and Merton but still hold the same sentiment, such as slacktivism and armchair citizenship, leveraging the negative implications of these terms with arguments that defend certain behaviors associated with them. Lastly, I will discuss how social media influenced political movements such as Occupy Wall Street and Arab Spring, drawing from the research of techno-sociologists such as Zeynep Tufekci and Sakir Esitti.

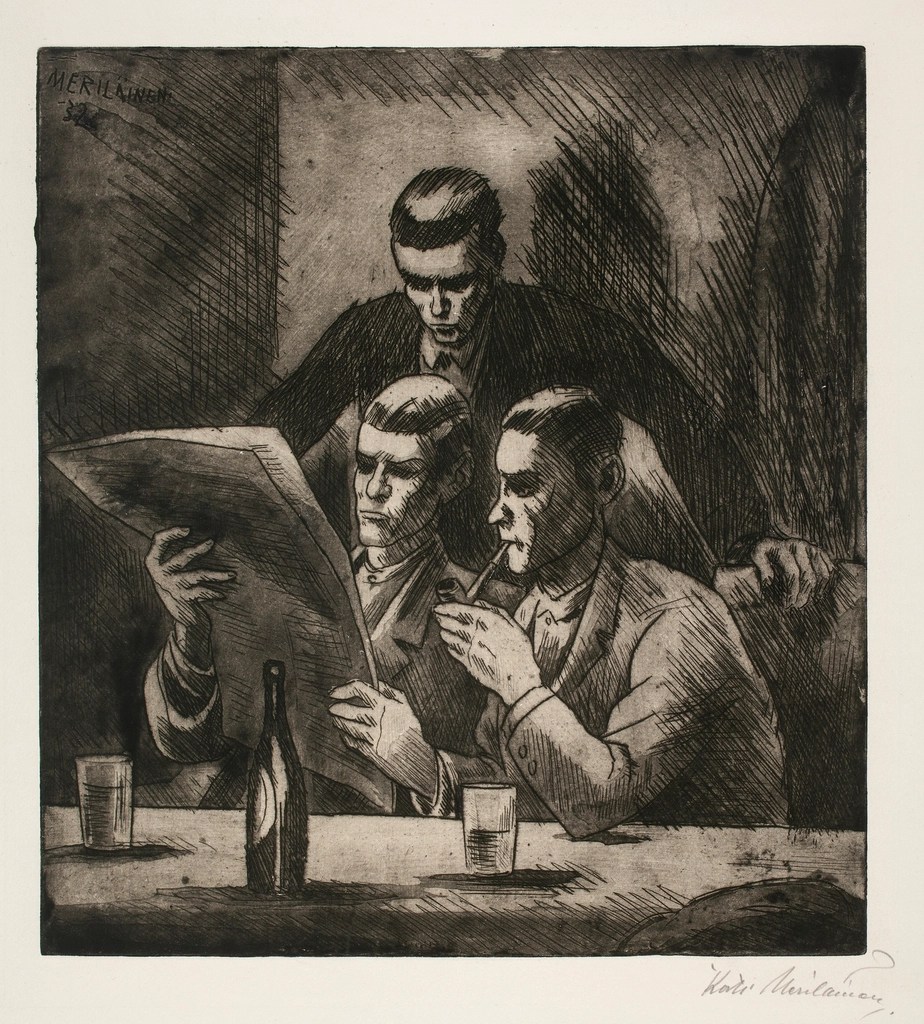

In their 1948 breakthrough article, ‘Mass Communication, Popular Taste, and Organized Social Action,’ Lazarsfeld and Merton wrote of the potential power of mass media, comparing the power of the radio with the power of the atomic bomb. They theorized that the enormous influence of mass media could be used for good or evil and that without adequate control, the latter would be probable (Lazarsfeld & Merton, 1948). It was in this same article that they coined the term “narcotizing dysfunction,” which they defined as the negative side effect of mass media that describes mass media’s narcotizing effect on an individual. They warned that this dysfunction may discourage a person from taking any actionable steps in favor of their political views and goals. Lazarsfeld and Merton (1948) wrote that exposure to an overwhelming dosage of information may serve to narcotize rather than energize the average reader. Since more time is devoted to reading and listening, less time is available for organized action. In Lazarsfeld and Merton’s own words,

He comes to mistake knowing about problems of the day for doing something about them. His social conscience remains spotlessly clean. He is concerned. He is informed. And he has all sorts of ideas as to what should be done. But, after he has gotten through his dinner and after he has listened to his favored radio programs and after he has read his second newspaper of the day, it is really time for bed (1948, p. 239).

The individual can feel as if he has done something merely by digesting information. However, since he has spent his energy on staying informed, there is little leftover for making any decision or taking action. Lazarsfeld and Merton (1948) warn that increasing dosages of mass communication may completely transform citizens from active to passive participants (p. 240). As their warning comes fifty years before the emergence of the internet and social media, it is imperative to consider how this theory can be adopted into this current age of increased mass connection.

As ‘social’ refers to human’s instinctual need to be in connection, and ‘media’ refers to the tools we use with which to carry our messages and keep us connected to other humans, the term ‘social media’ can be defined as the platforms from which we interact and stay connected through online exchanges (Safko, 2010, as cited in Esitti, 2016). As social media is related to Lazarsfeld and Merton’s narcotizing dysfunction, techno-sociologist Sakir Esitti (2016) warns that posting about political issues on social media “may give the social media users a false sense of accomplishment and serves as a self-satisfactory tool and narcotizes the participants” (p. 1025). The term “slacktivism,” which is the combination of the words’ activism’ and ‘slacker’ is, as Esitti (2016) points out, the modern-day term for narcotizing dysfunction theory as it refers to the dangers of mistaking posting on social media for an alternative to actual political participation. Another critical term that echoes narcotizing dysfunction theory in the age of social media is “armchair activism” or “armchair citizenship.” This term refers to how citizens engage in political action from the comfort of their homes, needing to provide only an email address and click send to join an e-petition or a cause. As Budish (2012) states, this process “dramatically reduce[s] the costs of participation, making joining a cause a trivial matter” (p. 750). In other words, since less effort is required to engage politically in an online space, we may feel as if we are contributing more than we are. As hypothesized by Kristofferson et al., social media “encourages low-effort forms of online activism (e.g., token support like retweets or changing profile pictures) that substitute for and suppress long-term activist efforts online” (2014, p. 1150). Put more bluntly, slacktivism makes us feel as if we are valuable assets to the causes that we care about when, in reality, we are making little to no impact while undermining the efforts of offline activists.

While this may seem bleak, many scholars do not take such a pessimistic approach. In the 2023 study, McDonnell, Neitz, and Taylor use latent class analysis (LCA) to reveal a class of citizens who have been given the opportunity to engage politically online where they otherwise would not have engaged at all (p. 2). This study predicts that those who fall under the classification of armchair citizens are typically associated with experiencing “ontological insecurity,” suggesting that their behavior as armchair citizens reflects more accurately on their sense that the world is moving too fast around them. They find comfort in online versus offline spaces rather than the narcotizing effects of social media (McDonnell et al., 2023). In this case, social media may be a refuge for citizens who experience anxiety in offline political spaces, giving them a voice and the opportunity to participate in political society. According to McDonnell’s study, while it is “possible that Lazarsfeld and Merton may have been right that ‘being informed’ sometimes prevents political social action,” it is not necessarily because armchair citizens are narcotized by their political awareness, but more likely a reflection of not having enough context or confidence to know how to act (McDonnell et al., 2023, pp. 13-14).

Further emphasizing the positive effects of social media on political engagement, Zeynep Tufecki explores the role that social media has played in social and political organization in her 2017 book Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. Tufekci, a self-pronounced techno-sociologist, considers how social media serves to benefit our experience. As stated by Tufekci (2017), “Digital technologies of connectivity affect how we experience space and time; they alter the architecture of the world…You no longer need to own a television station or be the publisher of a newspaper to make a video or an article available to hundreds of thousands or even millions of people” (p. 155). Regarding social action, she argues that social media is an invaluable tool for working-class citizens to form unity against the one percent. Tufecki (2017), who participated in the Occupy Wall Street movement, recalls that although this movement addressed one of the most significant issues in Western nations, the wealth gap, and should have been major news, it was largely ignored. She recalls that the movement was saved by “hastily set-up Facebook pages and Twitter accounts that shared news, pictures, videos from the protests, and even live-streaming of its general assemblies” and that through these platforms, the movement gained enough attention to become headline news (Tufecki, 2017, p. 244).

Through these online spaces, movement participants could critically discuss the issues of wealth inequality while gaining momentum with every follow, like, and share. As the audience for the conversation grew, despite the mass-media gatekeeper’s best efforts to portray the movement as unserious and harmless, the seriousness of the matter, as vocalized and framed by activists, eventually breached the surface of mass media. Journalists picked up the story, stoking the fire of the movement and highlighting its core message: the ninety-nine percent against the one percent. However, Tufecki (2017) admits that despite the movement’s achievements in organizing and rallying the masses, it led to little to no substantial changes in policy over the following four years. As quickly as the movement had risen, without the organizational infrastructure required to take the next steps toward congressional change, it held insufficient strategic capacity to threaten and dismantle policies protecting the one percent (Tufecki, 2017, p. 245).

Sakir Esitti expands on this criticism of social media activism, or, as he refers to it, the ‘Facebook Revolution,’ in his essay Narcotizing Effect of Social Media, using the example of the Arab Spring uprisings. In the demonstrations and riots that rose in the Arab world in 2010 in protest of long-standing authoritarian regimes, known as ‘the Arab Spring,’ many journalists credit social media as the catalyst that helped launch the movement (Smith, 2011, as cited in Esitti, 2016). Much like the Occupy movement, the Arab Spring activists garnered attention, educated participants, and organized action using social media. However, Esitti (2016) urges that the praise social media gathers for organizing movements should be more closely examined from a critical standpoint. While he acknowledges that social media is a useful tool for spreading awareness of issues and organizing the masses, he warns that there may be ‘unexpected’ outcomes to using these technologies (Esitti, 2016). For example, according to Esitti (2016), “During the times of social unrests and riots, increasing dosages of mass communication may transform energies of citizens from active participation to passive knowledge” (p.1017-1018). To clarify, echoing Lazarsfeld and Merton’s narcotizing dysfunction theory, spending excessive, time-consuming posts, blogs, and tweets on any given political movement may serve to narcotize rather than energize. This could explain the shortcomings of the Occupy movement; as participants were preoccupied with consuming and spreading content in the online space, this served to narcotize their abilities to think beyond the initial organizing in ways that would have been necessary to create tangible change. As emphasized by Esitti (2016), it is not a contingency that concerning oneself with an issue online will manifest in offline physical action and participation, and the very act of participating in movements online, displaying seemingly genuine concern, can become a way of clearing one’s conscience. He hypothesizes that citizens are more useful and authentic when spending their time in offline spaces, participating in rallies and decision-making processes (Esitti, 2016, p. 1025).

Thus far, I have explored the narcotizing dysfunction theory presented by Lazarsfeld and Merton in the context of social media activism, showcasing claims of scholars both in favor and against techno-optimism. Those in favor believe that mass communication technologies can meet various sociological needs, granting space for people with different social backgrounds and psychological dispositions to participate in political movements where they otherwise would be left on the sidelines. Those against it warn of the dark side of technology in mass communication, drawing attention to unintended outcomes such as political apathy and a lack of follow-through. They warn that if we cannot keep up with the speed at which mass media may give rise to our social movements, they may just as quickly lose momentum without the organizational infrastructure to move forward in an impactful way.

While social media has the potential to be beneficial for political activists, it cannot take the place of organized social action. As we are still learning how to harness the good of our global mass connection, we must proceed with caution. As we are in the early stages of playing with a technology that possesses great potential, still understanding how to harness the benefits while filtering out the adverse effects, we must proceed with caution. If we are wise, we may use it to aid in revolutionary movements that defend our freedoms against authoritarian governments and regimes. If we are careless and misguided, then the very technology created to connect and inform us will be our downfall, narcotizing us into apathetic and passive consumers highly aware of the issues of the world yet stripped of the energy and care to do anything about them.

References

Budish, R. H. (2012). Click to change: Optimism despite online activism’s unmet expectations. Emory International Law Review, 26(2).

Esitti, S. (2016, April 28). Narcotizing effect of social media. Academia.edu. Retrieved from

https://www.academia.edu/24842840/Narcotizing_Effect_of_Social_Media

King, L. (2019). Social Media: A Breeding Ground for Energy or Apathy? Perceptions, 5(1).

https://doi.org/10.15367/pj.v5i1.149

Kristofferson, K., White, K., & Peloza, J. (2014). The Nature of Slacktivism: How the Social Observability of an Initial Act of Token Support Affects Subsequent Prosocial Action. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(6), 1149–1166. https://doi.org/10.1086/674137

Lazarsfeld, P., & Merton, R. (1948). Mass communication popular taste and organized social action. Retrieved from

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Mass-communication-popular-taste-and-organize d-Lazarsfeld-Merton

McDonnell, T. E., Neitz, S. M., & Taylor, M. A. (2023). Armchair citizenship and ontological insecurity: Uncovering styles of media and political behavior. Poetics, 98.

Tufekci, Z. (2017). Twitter and tear gas: The power and fragility of networked protest. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14848

Leave a comment