Intro and a Disclaimer about Hellbenders

Exactly a year after Hurricane Helene, I’m sitting in the same house where I rode out the storm, rereading the fragmented account I managed to write on day 11, along with an intro about Hellbenders I drafted months later—because writing about my own experience felt selfish. I always told myself I’d come back and polish it.

Now, with the earth having made one full trip around the sun since then, I’m leaning toward simply posting it as it is—raw and disjointed, true to the state of survival my brain was in.

It’s taken me this long to write because I kept trying to center the piece on the Hellbenders—the giant salamanders native to these rivers—and how their already-fragile habitat was hit right in the middle of their mating season. It felt wrong, and honestly still does, to focus on myself when so many others lost so much more. I also know that’s a classic symptom of survivor’s guilt, and part of why I’m pushing myself to share my own account.

If you’d rather read about the Hellbenders, here’s a link to an article on how they were affected by Helene and how you can support their continued recovery. Despite this blog focusing on my personal experience, I am dedicating it to the Hellbenders— they’re amazing, ancient creatures, and they mean so much to Western North Carolina.

How I Made My Coffee That Morning

The first thing I noticed when I stepped outside on the day after was the American flag torn to shreds. The cushions I had left in a neat pile the night before were soaked and scattered across the porch. The second thing I noticed was that I was blocked in by a massive tree across the driveway. The neighbors were already readying their chainsaws. The power was out, but I figured it would be back on later in the day. My main concern was how I would make hot coffee.

I rounded all my brain cells and invented a technique that would be used for days to come. Two coffee filters and a funnel. Brilliant. Little did I know, less than a mile down the road, the four-lane had become a river.

A Classmate and Some Coworkers

When the tree was cleared, I hopped in my car in search of cell service. Driving downtown, I noticed groups of people huddled around restaurants and government buildings. It felt like something from clips of the Great Depression. It wasn’t until later that it occurred to me that those were the areas with working wifi. I saw a classmate huddled in a group outside the public library. He was on the phone, and when he saw me, he jogged over to my car. He looked equally bewildered. We exchanged a few “What the hell? Haha’s,” and then I said, “Guess I’ll see you later in class,” before driving off.

I found myself in the parking lot behind a restaurant, where I used to work. I couldn’t tell you how I ended up there. I guess it was half habit, half shock. When I pulled into the parking lot, I spotted an old coworker staring blankly ahead in his car. I honked my horn and rolled down my window, “Caleb!?”

He said he hadn’t heard from his managers and wasn’t sure if the restaurant would be open later, so he was waiting outside in case anyone showed up.

We stood leaning against our cars, catching up on the last 8 months of our lives. He was newly engaged and in the throes of dealing with a marriage visa for his Filipino fiancée. I told him about my semester abroad in Athens and my new job at an Indian street food restaurant meant to open in a few days.

Curfew

A woman pulled up and asked us if we knew of any open gas stations. We told her maybe the Exxon on Merrimon. It felt like we were back at work together, slipping so naturally into our service industry roles of pointing strangers in the right direction.

Another old co-worker pulled up and rolled down her window, “Gressa?? Caleb?? What the hell is going on?” She’d been driving around trying to find a gas station and was now on empty. She said she hadn’t eaten or had anything to drink all day. I ran back to my car to grab her the Trader Joe’s seaweed snack I’d grabbed for myself on my way out the door.

We all stood outside our cars making small talk. I got a text that there was a curfew of 7:30 for North Asheville. It was 6:45. Where had the time gone?

Riley followed me back to where I was staying. She lived alone with her two cats and without power or service, and didn’t feel safe in her neighborhood. She said there’d been an arrest across the street a week earlier. I still had propane, so that night we ate pan-fried dumplings by candlelight and caught up on our lives.

Apples and Bananas

The next day, I woke up in a panic, realizing that I had a work training at 10 am, but I hadn’t heard from my manager. I decided to try again to find some service. I noticed a crowd of people gathered around a radio at the fire station on Broadway Street. I parked on a curb behind a long line of cars and joined the crowd huddled around a radio. An officer was telling people to stay home and off the roads.

I heard people discussing in hushed voices that the National Guard was arriving later in the day. A woman behind me said there was water at Harris Teeter. I decided water was important.

I hopped back in my car to investigate Harris Teeter. The line to get into the grocery store could have wrapped around the building twice, but not knowing what else to do, I got in line. People around me were talking about the River Arts District, and a man behind me showed me pictures of the District swallowed by a gushing brown river. I recognized the hair salon, or at least the roof, where just earlier in the week I was considering making an appointment to get bangs.

Another woman in front of me was talking about moving from Texas to escape the onslaught of natural disasters. Another was discussing the best items to buy: apples, bananas, and grapes. Just as I was about to enter, someone yelled down that they were out of water—but sports drinks and seltzer remained.

Inside, I went straight for the bananas—but they were gone. I grabbed apples, a bag of grapes, a six-pack of Gatorade, and a 12-pack of seltzer water. At the checkout, I tried to run my debit card as credit—it didn’t work. I had $9. Two girls behind me overheard and insisted on covering the rest. They seemed equally distressed, their cart full of seltzer, fruit, and carbohydrates. I asked for their Venmo to pay them back when the internet returned. They said that it was only $10 and not to worry.

Plastic Money

Later in the afternoon, Riley and I ventured out to find gas for her car. We ended up in line at a mini-market. Riley had stashed cash away for rent and handed me $40 to go grab whatever I could find in the market while she waited in line for gas.

The market was picked through, and I found myself staring at Pringles side by side with another woman, squinting at the bizarre flavors that were left over. We shrugged at each other as I grabbed philly cheesesteak and she grabbed soy chicken. The line was almost an hour long.

I overheard bits of conversation standing in line and observed the mix of characters. People were striding in, acting like it was a big party, heading straight to the beer cooler, re-emerging with stacks of beer cases piled higher than their heads. A woman behind me talked loudly about how she and her boyfriend were prepared for this, that all their money was stashed under a floorboard in their attic. They had just finished distributing handfuls of cash to all their kids, who only had plastic money. She sounded proud, like finally her paranoia was being justified, and she wanted the world to know.

Note on the Doorstep

Just as I reached the checkout, Riley pushed through the doors and announced that the gas station had just run out of gas before she had reached any of the pumps.

When we returned to my place, there was a note on the doorstep with a sports drink on top of it. My sister had come to check on me, but I’d been out. In the note, my sister had asked if I’d heard from my parents out in Burnsville and my brother in Waynesville. I hadn’t heard from anyone.

Riley and I cooked frozen naan in a cast-iron with melted cheese on top and sat with it on the porch. A neighbor walked up and asked how I was doing. Because I was house-sitting, I didn’t know the neighbors well. The woman said that if Riley and I needed anything, she was living alone in the house down the driveway and to give her a holler.

A Subaru pulled up in the driveway; it was my sister and her two roommates. They were on their way to their friend’s brother’s house to grill dogs on the fire. I asked if Riley and I could tag along. I realized that all I wanted was to be among familiar faces huddled around a fire, cooking dogs.

The Exxon on Merrimon

Riley and I hopped in the car. Wren and her roommates were quiet. They were all nervous about driving back in the dark without any streetlights and with so many power lines and trees down. Riley filled the silence with her bubbly personality. Driving downtown Asheville the day after Helene felt like driving in an apocalyptic video game. We drove under power lines and trees and wondered periodically if we should turn back.

At one point, I got enough service to receive a freaked-out message from my best friend asking if I was okay, followed by a few reels. I sent her a message back, but it failed. When we finally made it to our friend’s house, we realized just how vulnerable it was, near the river, down a long driveway lined with trees. How lucky they were that their house was still standing.

A view of the French Broad River from their porch left us all speechless. Riley and I had grabbed some beers from the house, but didn’t have much to contribute otherwise. I saw a few familiar faces and felt my nervous system slightly relax.

My sister’s friend and her brother got news that their childhood home had been damaged in the flood. A few jokes were thrown around, but mostly the energy was heavy, and the silence between the jokes made the jokes feel out of place.

I realized that since running into Riley, I hadn’t had a moment to myself to take everything in. Although she carried herself with an easy confidence that made people guess she was older, I started to notice her youth—and how I felt suddenly responsible for her. I wondered how long we would be in this together; if she had friends in the area she would rather stay with, who were wondering about her— where she would be if we hadn’t run into each other.

On our drive back we passed the Exxon on Merrimon where many cars had gathered around. A man was standing up in the back of a pickup truck, yelling and taking cash from people. I took a video, unsure of what he was up to but feeling uneasy. Cop cars pulled in with their sirens on as we drove away.

That night, Wren decided to stay with me and Riley. We played card games by candlelight for a while. At one point, I looked at my hands and realized they were shaking.

Three Vultures

Nobody wanted to sleep alone that night, so we all piled into the same bed. We didn’t have service, but my laptop still had juice, so we looked through my pictures and videos. Observing life before all of this felt comforting and worlds away. The pictures were proof that these things had all happened, and that the person they had happened to had been safe with access to plenty of drinking water.

I fell asleep that night making a mental list of all the supplies I should track down: a whiteboard for communal water rationing, batteries, etc. That night, I dreamt that three vultures were circling the house, circling me, Wren, and Riley.

Marked Safe on Facebook

The next day, I walked to the fire department down the road, where there was a hot spot if you had Verizon, which I did. I marked myself safe on Facebook and posted on my Instagram story that I was safe. I didn’t stay long on Instagram, but it was enough to see some drone footage of the destruction.

I responded to the friends who had heard the news and had reached out to me. I messaged my grandmother and brother, whom I hadn’t heard from yet. I heard from my parents that they were safe in their community outside Burnsville, but the main bridge had collapsed, leaving them stranded along with their community.

They seemed in good enough spirits, reporting that there would be a helicopter soon, full of supplies that would land on the field I used to play soccer on in middle school. The community had already had two meetings discussing plans of action, and everyone had a job. I also received a message from my university saying there was emergency water and food on campus, and to come to pick it up if we were within walking distance.

A woman sitting on the curb next to me was crying with her face in her hands.

A House becomes a Hostel

On my walk home, I began to hear the helicopters. I wasn’t sure when they’d started, only that I had just started hearing them. I don’t know when I walked into a week later, or even two. Hurricane time doesn’t follow linear rules; all I know is that I woke up on day 11 and decided I needed to start writing everything down before I forgot it all.

I set myself up on the porch with a coffee. People played guitar on the steps, laid blankets in the yard. I found myself in a role that was exhausting to keep up with. I was basically running a hostel, responsible for the maintenance of a big, beautiful house and an elusive cat. Her name is Simone, and she is all white with round yellow eyes. She takes a while to warm up to you — she and I had had two weeks to get to know each other before the hurricane. Suddenly, her house became a shelter for a small community. She became a phantom, disappearing and reappearing behind the wood pile, the sawdust pile behind the tractor, the sewing room.

A friend of a friend had turned their porch into a charging station with coffee and oatmeal on Montford Avenue. People would go over at 10 am to listen to the radio together on his porch, charge their electronics, and drink hot coffee.

One evening, Wren and her roommates came back from a meeting in West Asheville, where many things were said— among them, rumors that people with masks and baseball bats were walking up and down the roads and the neighborhoods.

Nail Clippers and Looting

When a friend’s mom from out of town showed up with a truck full of potable water, we all stopped rationing. Supplies were coming in. I was sitting at the fire station responding to friends and family when someone dropped off gallon jugs of water and apples. I looked up from my phone, unsure if it was okay for me to take them. “Yes,” the man said enthusiastically, “this was meant for you.” I grabbed a gallon and a few apples and headed home.

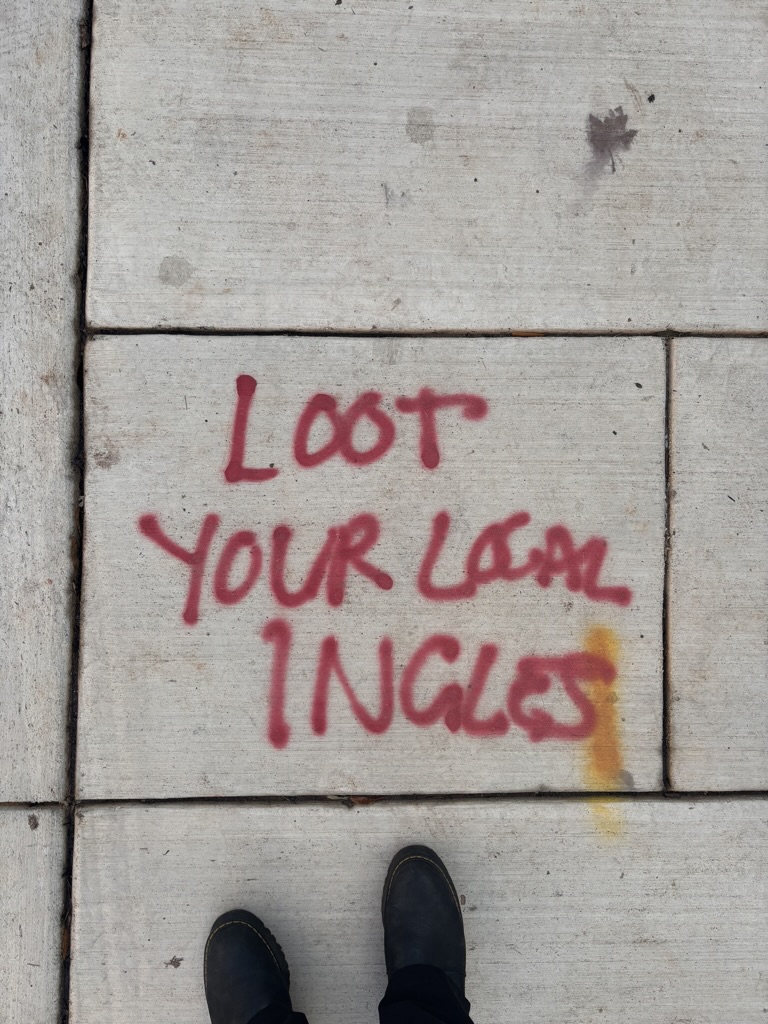

At 10 am and 4 pm, there were broadcasts, and we’d all gather around a radio and listen to updates— from the lists of missing people to rumors of looting and arguments about what qualifies as looting. A frazzled journalist asked over the radio, “If Ingles has locked their doors while produce rots inside and a hungry family takes the food, is that qualified as looting?” The officer replied, “Looting is looting.”

I told myself I would finally finish reading that book. I never did. I drank every day, but somehow I stayed sober. A somberness underlay everything. But when we laughed, we belly laughed. One day, we were all discussing things we missed from normal life. We were playing Monopoly with beers as helicopters flew overhead— for some of us, it was washing our hair, listening to music that wasn’t already downloaded, or playing video games. I said it was cutting my toenails. Everyone looked at me, “Gressa, you know that you can still cut your toenails, right?” But I couldn’t find nail clippers anywhere, and it just felt like one more stressful thing that I couldn’t handle.

Flushing Toilets, and Everything Else

We discovered a gravity-fed rain irrigation system in the garden and stopped gathering water from the pool down the road. We held a community meeting about flushing toilets with buckets as soon as we’d used them.

The Indian restaurant I’d just been hired at became a little resource hub. I went to volunteer and was given free naan and paneer skewers. I nearly cried.

My first shower in weeks felt spiritual. I swore to myself I would never take another shower for granted as long as I lived.

I realized who my real friends were, who bothered reaching out when they heard. I learned a valuable lesson in how to show up for people experiencing a disaster: as long as you do it in a way that is genuine, it matters. It really matters.

My whole life has been a lesson in community— growing up in one, holding onto friends for decades. Times like these are when they matter. I mean, they matter all the time, but you know what I mean. Something about the importance of community… I don’t know. I’m tired.

P.S. Photos are a mix of mine and my sister’s (thank you, Wren!)

Leave a reply to seegressagrow Cancel reply